#37: Henri Lefebvre, Herve Guibert, Gene Wolfe

Good morning friends. The weather has finally sunken into the double digits, providing a physical and psychological reprieve. After this newsletter hits your inbox I will likely emerge from my cave that has provided me with so much shelter from the heat, inflate the tires of my favorite bicycle, and ride to the springs, to the dam, and to the lake. I will swim, look at birds, lay in grass, and take a last look at the wilting, browning flowers planted alongside the hike and bike trail. I will hope that, for just a second, all the vegetation will similarly take a moment to rebel against the sun that has scorched them and bleached away all their chlorophyll and they will spend their final reserves of energy to create a green vibrancy before everything turns brown. I’m not sure plant life works that way though, unfortunately.

Maybe this is also the temporary end of introductory paragraphs packed with climate complaints. Maybe it’s the beginning of something more substantive or interesting. Wouldn’t that be nice?

Immediately below are a couple live recordings of the Brain Police from Japan, a kind of folk-rock band who were booted from their record label for being too politically left. These recordings are amazing. Below that are some book and film reviews. Have a listen and a read and tell me if any thoughts of your own arise:

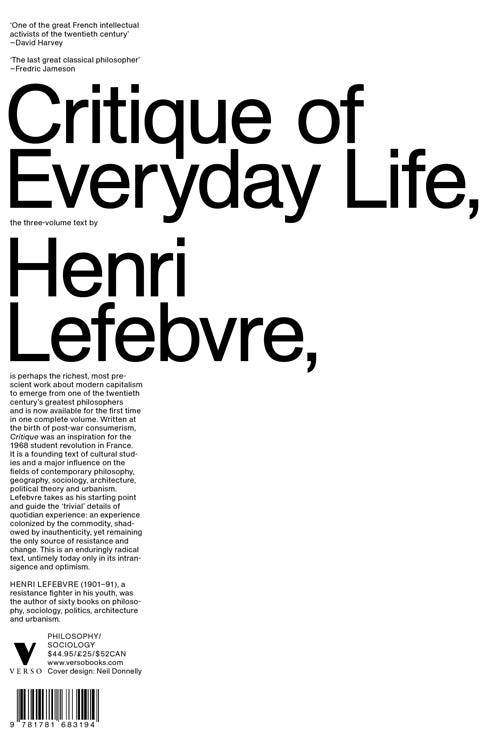

Critique of Everyday Life Volume III by Henri Lefebvre

I have finally finished the entirety of Lefebvre’s Critique of Everyday Life. I really struggled at times, especially during the second volume, but I’d like my final report to indicate that this is a masterpiece. Lefebvre created a theory of everyday life across his entire life, the first volume coming in 1947 shortly after the second world war, the second in ‘61 anticipating the revolutionary spirit that would take hold of the youth seven years later, and the final in ‘81 when the alienation produced by consumer society was reaching a saturation point.

As I’ve said before while reviewing volumes I and II, the major lasting contribution of this work in my mind is Lefebvre’s advocacy for a non-dogmatic Marxism. Lefebvre left the Communist party “from the left,” as he wrote. Perhaps capital-C Communism has failed (it certainly has in so many ways), perhaps it has not completely, but Marx’s writings remain a valuable source of inspiration and provide a beautiful trajectory in the pursuit of a better world. Likewise, I find myself thinking so much more often about alienation — locating it in our relations to each other and to objects, diagnosing it in art. It’s one of the great social ailments produced by and improved upon by each stage of capitalism and to have spent so long reading about it will bear a heavy impact on the way I continue to think about the world as I flow through it.

Historically and sociologically, what Lefebvre does so well is trace the “colonization of daily life,” the capture of daily life by commerce. For example:

Contrary to the Marxist schema predicting the formation and investment of large capital exclusively in what is called heavy industry (iron and steel, chemicals, etc.), many of the most powerful global enterprises established themselves in daily life in this period: detergents and cleaning products, drink and food, clothing. Some curios misunderstandings resulted: blue jeans, produced by these global enterprises — possibly in countries such as Hong Kong and Singapore, whose proletariat was super-exploited — were regarded by young people as a symbol of freedom, novelty, and independence.

Similarly:

Take, for example, the mechanization of the bath. Capitalist and bourgeouis Europe made the transition from public baths, meeting-place and site of social life, to the bathroom, in which each member of the group is isolated. The mechanical function of ‘cleanliness’ was enhanced at the expense of bodily relaxation and restoration on the one hand, sociability on the other. Antiquity, by contrast, switched from the private bath to magnificently equipped public (thermal) baths.

This is something I think of often when travelling in Latin America and I see the big central parks within each city that serve as actual community spaces — something that feels generally discouraged in the U.S.

I leave you with the slogan of ‘68: changer la vie. Always be self-reflective, always be self-critical, always situate yourself and your thought within the many contexts that envelop you. Likewise, always be a utopian — “for what is possible to come to pass, must we not desire the impossible?”

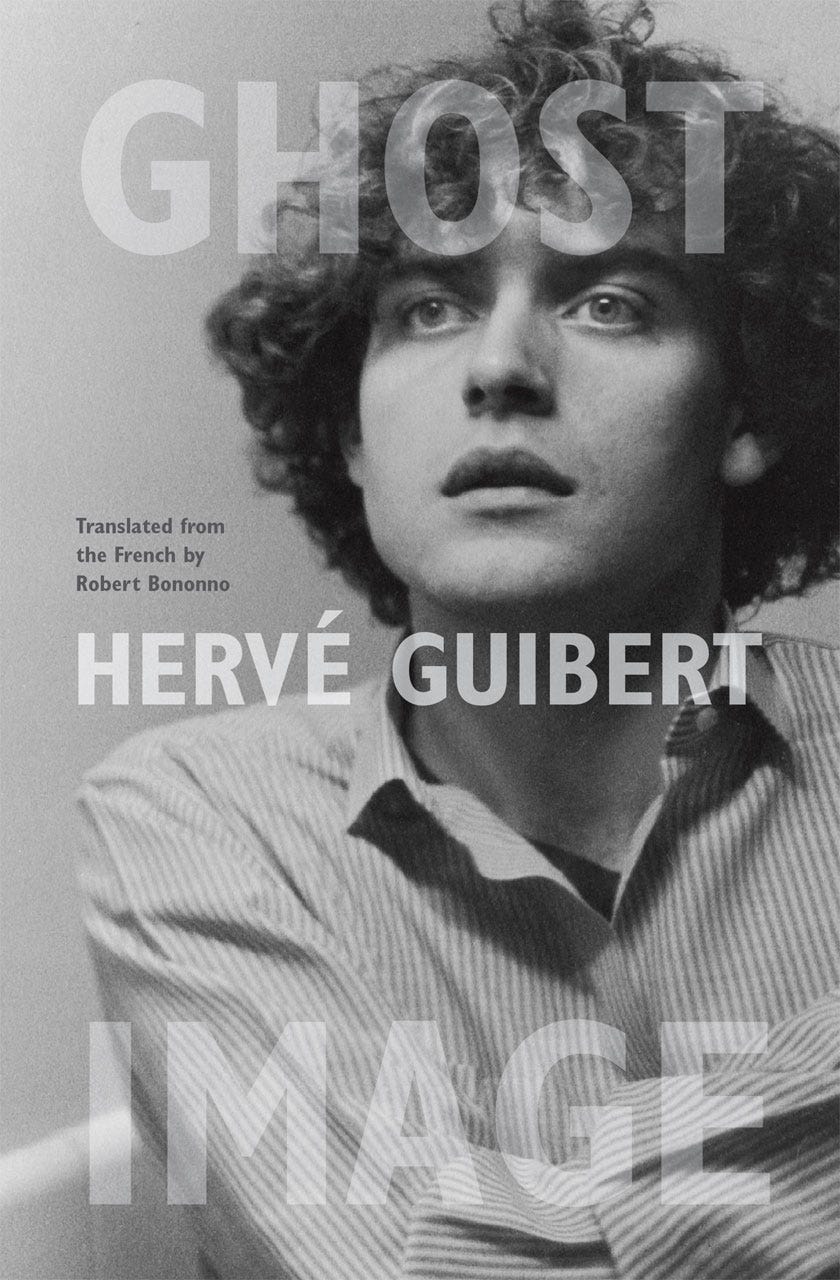

Ghost Image by Herve Guibert

I recently wrote about Herve Guibert’s stunningly beautiful Modesty and Shame, a short film/video diary documenting his last year alive before his death from AIDS.

My friend I saw that film with (hi!) wanted to read Guibert’s Ghost Image afterwards, in which Guibert theorizes photography and writes about his relationship with and feelings towards photography. It’s a response to Barthes’ book, says the blurb on the back, but I haven’t read much Barthes’ so I can’t write to that.

More clear to me is the genealogy from Proust to Genet to Guibert — all beautiful writers that make me feel like my personal depth of feeling could not be more shallow. I don’t know how they FEEL so much but clearly there is something wrong with me since I cannot take a picture of myself in a hotel room mirror and think of it as so important and romantic. Maybe this depth of feeling that they create in their writing is deviant? Men are not supposed to have this much feeling — I suppose the sensitivity is its own form of violence.

The first essay, the one about the ghost image, is a story about Guibert taking a photo of his mom composed in a way that goes against the image his dad has painstakingly created of her, truly oedipal. User error prevents the film from developing and the picture is no picture at all, but an absence of a picture, a ghost that haunts them forever. And now I finally understand what philosophers are getting at when they harp on and on about absence and presence.

It’s 160 pages and every story is about 1-5 pages. Worth reading if you have ever enjoyed taking a picture in your life.

Movies!:

Werckmeister Harmonies by Bela Tarr

Werckmeister Harmonies is a film that aims to balance what can be understood and what cannot and what that does to a person. The unknown, a whale in this film, catalyzes the pursuit of knowledge in some and produces fear and a resultant fascism in others. However, in each of us, and in each other, there is always an unknown, an other, that begs comprehension and compassion. There is this incredible scene straight from Levinas where a fascistic revolt halts as soon as a face becomes visible/legible.

Similarly striking to me is the scene in which the protagonist is dictated by his fascist aunt to put the sons of the policeman to bed and they are yelling and banging pans and waving weapons to the soundtrack of nationalistic classical music. It’s pure poetry, really.

Taxi Zum Klo by Frank Ripploh

It translates to Taxi to the Toilet. I had long thought Germans couldn’t be funny, but there may be a few special exceptions. Maybe the gays can be funny. Herr Ripploh loves cruising but winds up with a monogamous boyfriend who suffocates him with repetitive love and niceties (“how was your day?”). It’s tender, light hearted, reflective, super chaotic, fun, and has actual dick-sucking and cumshots in it. It’s hot and it’s beautiful. I could watch it over and over again.

To make it especially relevant, Herr Ripploh is an elementary school teacher which makes this film a radical manifestation of the worst fears of the conservatives currently waging that culture war right now. It cuts from dick-sucking scene to Herr Ripploh teaching class. I can’t imagine how awful some people would find that juxtaposition, despite its absolute banality in reality. I was lucky enough to see it on a totally brutalized 35mm print but you can watch a far cleaner restoration on vimeo here.

Chile ‘76 by Manuela Martelli

A chance encounter with the face of another, again in the Levinasian sense, and what that face asks of the protagonist and the viewer. There is this slow reveal of the “criminal” as revolutionary both in terms of verbal and visual language (first we are only shown a leg, then a torso, eventually an obscured face, and finally the bare face) that brilliantly humanizes the character and the revolution for a reactive viewer and the bourgeois protagonist.

To see a face is to be asked to protect it. Fascism demands that we reply in the negative.

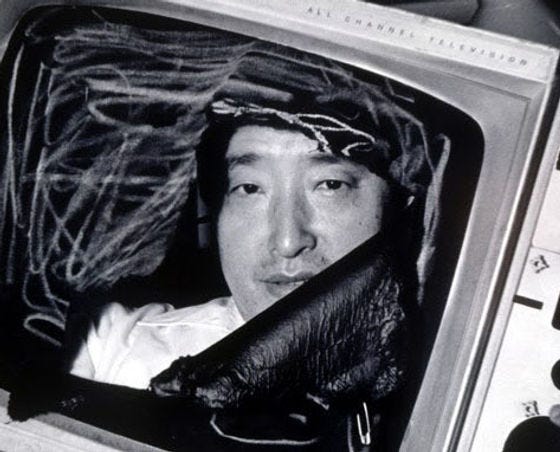

Nam June Paik: Moon is the Oldest TV

This is the greatest art documentary I have ever seen. I have a giant soft spot for John Cage and Paik was heir to so much of Cage’s wisdom and experimentation, but mixed that with being THE enfant terrible of the art world. What’s not to like? You can watch the full movie for free on PBS’s website.

Swallowtail Butterfly by Shunji Iwai

This is a fast favorite. An amateurish, sweepingly ambitious, nearly 3 hour long Japanese near-future film with all the trappings of cyberpunk without any of the technology. It’s in English, Japanese, and Cantonese. The English is mostly horrible and it feels like they’re probably just memorizing sounds, the acting is mostly pretty awful and over-the-top. The story doesn’t make a ton of sense and the tone of the film changes frequently. HOWEVER, despite all of this, the story is also a beautiful one of immigrant resistance and community resistance against the alienating force of capital and the destructive power capital has to those who succumb (all of us). It’s ambitious beyond itself and if there is one quality that is important in art to me, its ambition. Swallowtail Butterfly seems to have a monopoly on the stuff.