Hello beautiful friends. I’d like to begin this newsletter on this blessed Sunday by telling you that I have some of my own new stuff to share before I ramble on about books and movies. For a little bit now, I’ve been working on a new band with some friends. It started out as Barry and me, but Barry moved to New York. In the end, it’s me, Jake, Sam, and Bacio. It’s called Beyond State Power. Rhizome and Human Rights were the rejected names. Ruby wanted it to be called Cleveland Dog. Check it out below or on bandcamp.

If you care to read the entire lyric sheet and you can read my handwriting, you may notice that the bottom right corner lists the authors I was inspired by: Amelia Rosseli, Diane Di Prima, Viktor Shklovksy, Adi Ophir (who I write about in this post), Eyal Weizman, Sahar Khalifeh, and David R. Bunch. The band’s name was also appropriated from Abdullah Ocalan’s Beyond State, Power, and Violence which I wrote about back in October.

The last couple weeks have been fun. Last week there was a big comedy festival in town and I ended up spending some time with comedians I liked and others I didn’t know before but quickly learned to like. Watching a comedian’s personality switch as they walk on stage is pretty wild and must be similar to the experience some people have when they see a punk band for the first time after meeting some nice, seemingly well-adjusted individual.

While I play at making anarchist music, protesters all over the nation set up tents on their university’s campus and are tear gassed by the police. Universities cancel graduations, block their Muslim valedictorian from speaking, tell their Jewish students that the university is not safe for them, and send in state troopers to arrest the students who dare to think, act, and speak against them.

Israel continues to attack hospitals and medical infrastructure. While hospitals stand, Israel tortures and mutilates Palestinians inside them and buries them alive right outside. They use their Caterpillar D9 Bulldozers to shave off the topsoil of Palestinian agricultural land and create a desert where they set up military their outposts. They destroy vital greenhouses and block aid. Ecocide is genocide.

Genocide is genocide. How can one escape the centripetal force of tautology and continue to produce meaningful insight that mobilizes action and changes viewpoints? Will such thought ever be able to overthrow the profitability of war or the benefit of the strategic capture of land in the “Middle East?”

The Order of Evils by Adi Ophir

Adi Ophir is one who escapes tautology. He flips moral philosophy on its head by shunning the transcendental and building a framework up from the negative. “This treatise aims to…attribute to human beings full responsibility for what they do to other human beings, without letting them escape to heaven or hell, but also without letting them retreat from the historicity of social existence to the depths of the human soul and its mysterious, unchangeable nature, or to the enigma of human freedom.”

So begins Adi Ophir in his challenging and thorough reorientation of morality from the theological to the ontological. Instead of a moral philosophy that asks us to pursue the good, Ophir proposes a moral philosophy that has us look in the face of evil, the face of so much suffering, and respond to it. It’s a moral philosophy borne out of the cultural memory of Auschwitz and the desire to respond to the endless siege of Palestine by the author’s motherland.

Ophir deconstructs the moral philosophy of Kant, Hegel, Spinoza, and especially Levinas. Remember, however, that deconstruction is not an attempt to dismiss something, but a desire to critique it in the name of improvement. Evil as Ophir names it is the distribution and social production of suffering. This creates space for a sort of marxist science of ethics that surpasses Marx’s own.

It’s 700 pages of moral philosophy and I don’t quite know how to write about it. It’s incredibly challenging and quite exhausting honestly, but absolutely brilliant. If you’re into this sort of stuff, it’s worth a read. Instead of prattling on, let me just quote below the greatest critique I’ve read so far of human rights frameworks — yeah I like it even more than Agamben’s:

Because so much of moral discourse is organized around the concepts of justice and injustice, and the concepts of rights that accompanies them, even the most urgent dealing with the most horrible evils that are denied by no one is mediated today in Western societies by a rhetoric of justice and injustice with the framework of human-rights discourse…When rights are defined in this way, transgressing them is a morally improper action by definition. In order to defend victims of these and other kinds of state terrorism, exploitation by the capitalist market, and the oppression and humiliation produced by both, we incessantly widen the realm of reference of the concept of right and include it in the evil that befalls the victim in a particular case: tortured detainees have a right to a fair investigation; the starved have a right to bread; the unemployed have a right to work; chronic patients have a right to die in dignity; women have a right to abort their fetuses, and fetuses have a right to be born; the systematically murdered have a right to live, and animals, too, have a right to live….

Evils become violated or denied rights that must be rectified; the right precedes the evil and is the condition of the possibility of talking about it, making it visible, and showing it to others. Looked at from the perspective of rights and their denial, evils tend to conceal their sui generis institutionalized mechanisms of their production and distribution. The denial of rights is presented as an infringement on a normal routine: the arrest and investigation are morally authorized, only torture is declared improper; a curfew of a city under occupation is acceptable, on the shooting of those who violate it is noted…

The discourse on rights normalizes and legitimates existing systems for the production and distribution of evils at the price of a clear distinction between the proper and the improper within those systems. Its advantage is that it allows one to isolate what seems, from a certain point of view, the most urgent moral matter and give it a relatively efficient treatment. Its main weakness is that it tends to legitimate, and perhaps also nurture and enrich, the system that creates the conditions for the appearance of such urgent cases, sometimes even produces them directly, and, within that, increases both moral blindness and the narrowing of the horizons of the moral discourse.

I’ll be keeping this book near me. We are forever living on the seventh day, the day in which God stepped back from his creation to rest. Pursuing his favor will continue to fail us. The only way forward is through meeting the gaze of the other and doing what you can to end their grievous and superfluous suffering.

Michael Kohlhaas by Heinrich Von Kleist

Michael Kohlhaas was a 16th century horse trader who was at once one of the most righteous and appalling individuals of his time. Until the age of thirty, Kohlhaas was an ideal citizen, but when he was lied to and wronged by some miscreant royal, he followed his sense of justice to excess.

When, one day, Kohlhaas passes through some small township on his way to sell some horses in Dresden, he suffers an abstract stop from some border guard asking for his permit. He has never had to have a permit before in all his years trading horses, but he agrees to leave his horses at the castle and ventures alone to Dresden to acquire the permit in question. When he arrives in Dresden, they tell him no such permit exists. Mildly annoyed but amused nonetheless at the harmless prank, Kohlhaas returns to the castle to retrieve his horses. He finds his horses overworked and underfed and his hired hand that was travelling with him has been physically abused and kicked out of the castle.

Kohlhaas demands retribution for the horses — they shall be fed and groomed back to their original condition. The noble family denies him this and Kohlhaas pursues justice at the court and is spurned once again. Here is where one could cut their losses, standing before the beastly and abstract gatekeeper of the law. Kohlhaas could have about-faced and returned home. However, Kohlhaas believes in justice. He sells his house, he buys an army, and he attacks the castle. Though nearly everyone else associated with the castle is brutally murdered, the most guilty noble gets away. The noble flees to one town and to the next as Kohlhaas burns them all down. Kohlhaas’s wife dies, his hired hand dies, as do hundreds of others. It all piles on but Kohlhaas is unbothered in his single-minded mission for justice. He eventually gets something that he feels fine calling justice. It’s a brief novel (112 pages) and maybe you’d actually read this one, so I won’t spoil it. Kafka made two public appearances in his life and he spent one of them reading entire passages from this book.

In the literary tradition, Kohlhaas is a hero, but isn’t he another bourgeois merchant chasing surplus value? As he pursues justice, the death of his wife and the death of his laborer seemingly do nothing to his mental landscape. It’s a complicated and hilarious book that asks what the limits of justice are. Kohlhaas recognizes himself as someone who has been cast of the justice system because he received no protection from the law, thus identifying himself as some sort of 16th century homo sacer.

Kohlhaas even burns down the entire town of Leipzig. One time Glue played Leipzig. After the show the promoter asked me how much money we wanted. I asked him how much the show made. He told me “it is about $1000.” I told him to go count and tell me how much it is. He came back a full thirty minutes later and told me “it is about $1000.” After some annoying back and forth, I had had enough with weird German behavior so I told him I’d take the whole $1000. He told me he could give me $100. After more back and forth, I walked away with $100. I don’t know what the other $900 went to. Probably buying more Israeli flags or something. The promoter could tell I was annoyed and he wanted to make it up to me so he told me that in the morning he would make me a very special breakfast — the best breakfast of tour. I woke up at 6 am to him banging pots and pans and listening to the most horrid playlist that alternated between pop punk and stadium crust. “At least he’s actually cooking something,” I thought to myself after weeks of weird European breakfasts. Finally, after 2 hours of laying in bed hoping to fall back asleep, he told us breakfast was ready. It was the same breakfast you get at every German squat — store bought bread with weird vegan spread. I could have burned down Leipzig too.

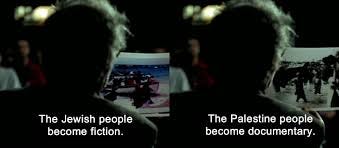

Jean Luc Godard’s Notre Musique is a brief meditation on destruction and a deconstruction of the narrative structures we use to understand destruction. It’s the only film in which the Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish makes an appearance and is worth watching for that alone. You could watch it in 80 minutes on youtube.

Vera Drew’s The People’s Joker is a free-use parody film that exists in the Batman world. It’s an autobiographical, coming-of-age, trans-becoming story. It’s incredibly funny and tender and goes to show that if you really mean it, you can make a pretty compelling film for a lot less money than Hollywood amasses for its productions.

Mahjong is Edward Yang’s gnarliest. It’s his gangster film that further elaborates on the corruption of Taipei and capitalism in general. Here, we really see Yang leaning into the globalization of Taipei with tons of Western actors present. It’s unsettling and harder to watch than every other Yang, but it’s Yang at his most bitter and furious. The violent climax of the film is absolutely jaw-dropping. Another peak from a director who continuously found new dimensions of storytelling to conquer.

I really want a taupey linen suit that I can beat to shit like the one feature in La Chimera. The film could fit well on a list with Long Day’s Journey Into Night and Drive My Car — contemporary films that mine the auteur tradition. La Chimera, to me, felt a bit more substantive than the others on that list as it seeks a return to a more communal tradition of Italy, eternally in connection with the dead.

No Skin Off My Ass is a gay skinhead flick. There’s an interesting reversal here where the viewer expects the skinhead to be the fascist, but the hairdresser who lusts after the skinhead and the skinhead’s sister perform the actual fascism. The sister is a filmmaker who bosses people around and slaps them, demanding that her brother be a fag. Authorial control is always fascism! In another fascistic twist, the hairdresser tries to imprison the skinhead after luring him home. There are at least two cumshots. It’s a cute 80 minutes.

Morvern Callar absolutely blindsided me. Morvern Callar’s boyfriend commits suicide one day around Christmas and leaves behind enough money for his funeral and a finished manuscript for a novel to be submitted to a list of publishers. Morvern instead disposes of his body herself and uses the money to reinvent herself as she refuses or struggles to process his sudden death. She meanders through Europe, hanging out parties, going to raves, walking through Spain, all while listening to a mixtape he left behind for her. It’s a confusing movie that resonates with me as I continue to struggle to process the deaths of the friends I have lost — it’s horrible to feel so little but I will always feel like, for some reason, my depth of feeling is far more shallow than everyone else’s when our friends die. It’s an alienating and odd experience.

Edward Yang’s final work before his death from colon cancer. A refined culmination of all of his anger and hate towards neoliberal, globalizing Taipei that is so palpable in Mahjong or Confucian Confusion combined with his contradicting love for family and people in general. A masterpiece and his easiest work to digest. I will always love Yi Yi. I wrote about it last in December 2023. Thus ends the Edward Yang series at the theater that I go to here. What a treat to be able to watch five of Yang’s incredible films over the past couple of months.

We Jam Econo is a documentary about one of the greatest bands that punk ever produced, the Minutemen, and a devastating reminder that at any given moment, the beautiful people you take for granted could go. Tell your friends you love them.

I love you, friend.

To cleanse your palette after you maybe listened to a second of my new band, enjoy something else. A beautiful acoustic performance by The Minutemen, one of the few bands to meaningfully challenge the parameters of punk. A devasting performance by SDS in Nagoya as part of the Punk and Destroy gig series that aimed to more seriously bring politics and anarchism into the Japanese punk scene. A brief video of the stridently anticapitalist and anarchist Assuck at the same venue in Nagoya two years later, featuring SDS’s Kenichi stage diving. Klaus Dinger’s late 90’s continuation of Neu! that proved the man would never run out of interesting ways to make beautiful, compelling, and engaging music that sounded new every time.

Have a nice couple of weeks <3

you had me at 16th century horse trader... burn Leipzig!